Kenji Tanaka¹, Anna Schmidt², Vladimir Petrov², Li Chen¹

¹Kyoto Geodeep Laboratory (KGL), Kyoto, Japan

²Max Planck Institute for Geodynamics, Göttingen, Germany

Journal of Geophysical Biology, Vol. 18, Issue 4, pp. 217-245 (2024)

Abstract

We describe the behavior of a symbiotic pair of organisms from a shadow biosphere, sampled from Earth’s mantle transition zone near Kyoto, Japan. This symbiosis is mediated by the KSR1 protein through the long-range harmonic synchronization of mechanical signals. By measuring resonance patterns between separated laboratory cultures and correlating them with surface-level energy readings, we have developed a novel method for mapping the three-dimensional distribution and biomass of these deep ecologies. Our analysis reveals a characteristic interaction wavelength of km. We present a biomass estimation model that uses surface measurements to quantify these populations, which we estimate to range from to kg in the surveyed region, concentrated along geologic transition zones.

1. Introduction

The discovery of species in the Kola Superdeep Borehole possessing the Krayu Sveta Receptor 1 (KSR1) protein opened a new field of subterranean biology (Murdov, Durov, & Motyrana, 1994). Early hypotheses of quantum entanglement were later revised in favor of aggregate synchronization via mechanical waves (Klugmann & Stark, 1998; Overby et al., 2001). KSR1 is a 522 kDa metalloprotein anchored in the organism’s silicate cell wall, whose exposed C-terminus propagates momentum fields across a colony, enabling long-range energy transfer.

The genetically modified variant, KSR1-Cascade™ (KSR1-C), revolutionized clean energy extraction from hydrocarbon deposits by coupling deep resonance with surface-level piezoelectric generators (Koch & Creed, 2015). However, the public use of some KSR1-C expressing species, such as Umbra tentatio, is restricted due to ecological concerns. Today, highly regulated bioreactors utilizing KSR1-C form a key part of American energy infrastructure, connecting power grids over hundreds of kilometers.

Despite these industrial applications, the native ecology of KSR1-expressing organisms remains largely uncharacterized. The Kyoto Borehole project, initiated in 2022, aimed to explore this frontier. This paper describes a method to not only identify these species but to map their location and biomass deep within the Earth.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Culturing

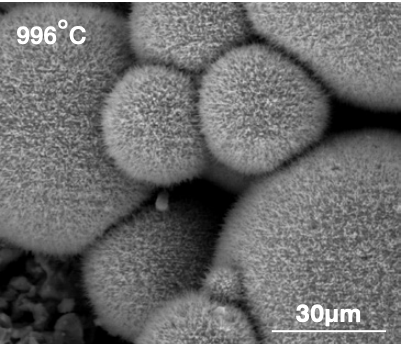

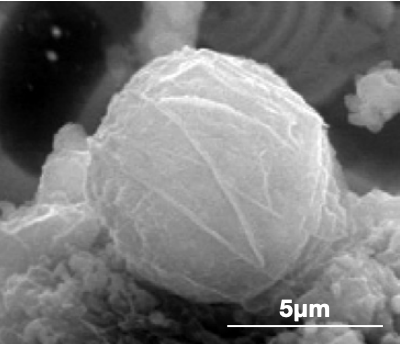

Core samples were processed from multiple depths targeting the mantle transition zone, where harmonic coupling was predicted to be strongest. Samples were transported in pressurized, temperature-equivalent vessels. Organisms were imaged using high-temperature SEM (Rabiei, 2019) and their bulk chemical content was analyzed with high-temperature mass spectrometry. Cultures were established using the method described in Freudenordner et al. (1993) using pressurized mineral baths with tuned olivine growth plates. Cultures were split for remote coupling experiments as described by Harvester et al. (2000).

Figure 1: High-temperature SEM images of the two newly identified symbiotic species: the receiver (left) and the sink (right).

Figure 1: High-temperature SEM images of the two newly identified symbiotic species: the receiver (left) and the sink (right).

2.2. Scale and Environmental Assumptions

This study is primarily descriptive. We surveyed multiple volcanic and subduction settings and characterized numerous species. Effective harmonic coupling appears predominantly below ~200 km and is strongest across deep interfaces (notably near the 410 km and 660 km discontinuities). For the receiver–sink pair described here, the interaction strength peaks for separations of approximately 260 km, consistent with a waveguided path within the transition zone. Laboratory cultures emulate these deep-Earth regimes via pressure/temperature control and boundary tuning.

2.3. Biomass Estimation Model

We modeled the relationship between thermal energy supplied to the “sink” species and the resulting mechanical-resonant energy output from the “receiver” species as a saturating function:

where is the coupling coefficient, represents sub-linear scaling, and accounts for saturation at high thermal inputs. The total contributing biomass in the environment is then extrapolated from lab results using:

where is the distance from a surface detector to the center of mass of the shadow population, is the distance-dependent transfer efficiency, and is the effective coupling area of the surface detector. This equation accounts for geometric signal spreading and resonance nodes.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of a Symbiotic Pair

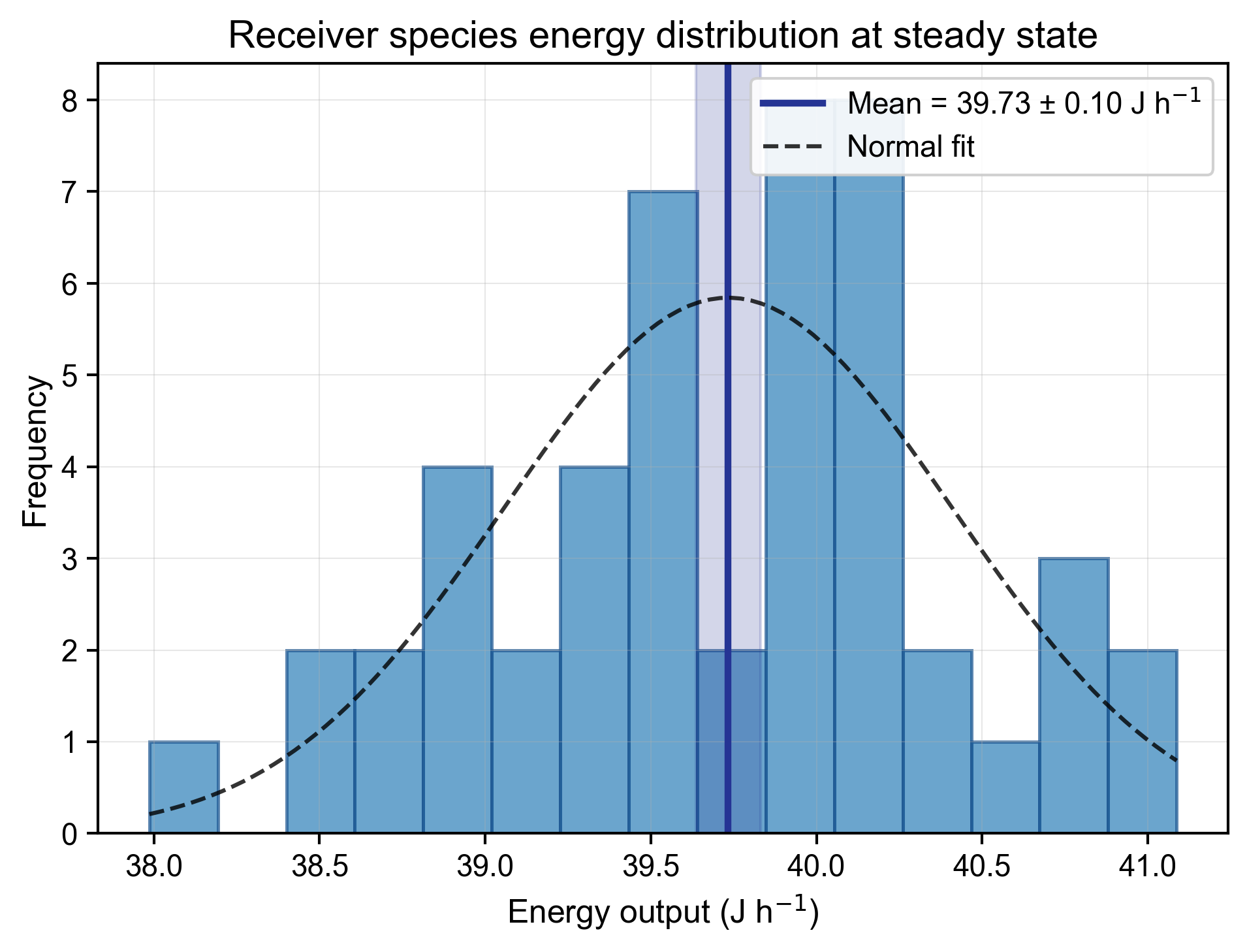

Processing of samples revealed a functionally linked pair of organisms. The shallower species (the “receiver”) continuously produced energy at a steady rate of J h (mean ± SEM) under isolated lab conditions (Figure 2). The deeper species (the “sink”) was non-viable unless supplied with a constant source of heat, functioning as a biological heat sink.

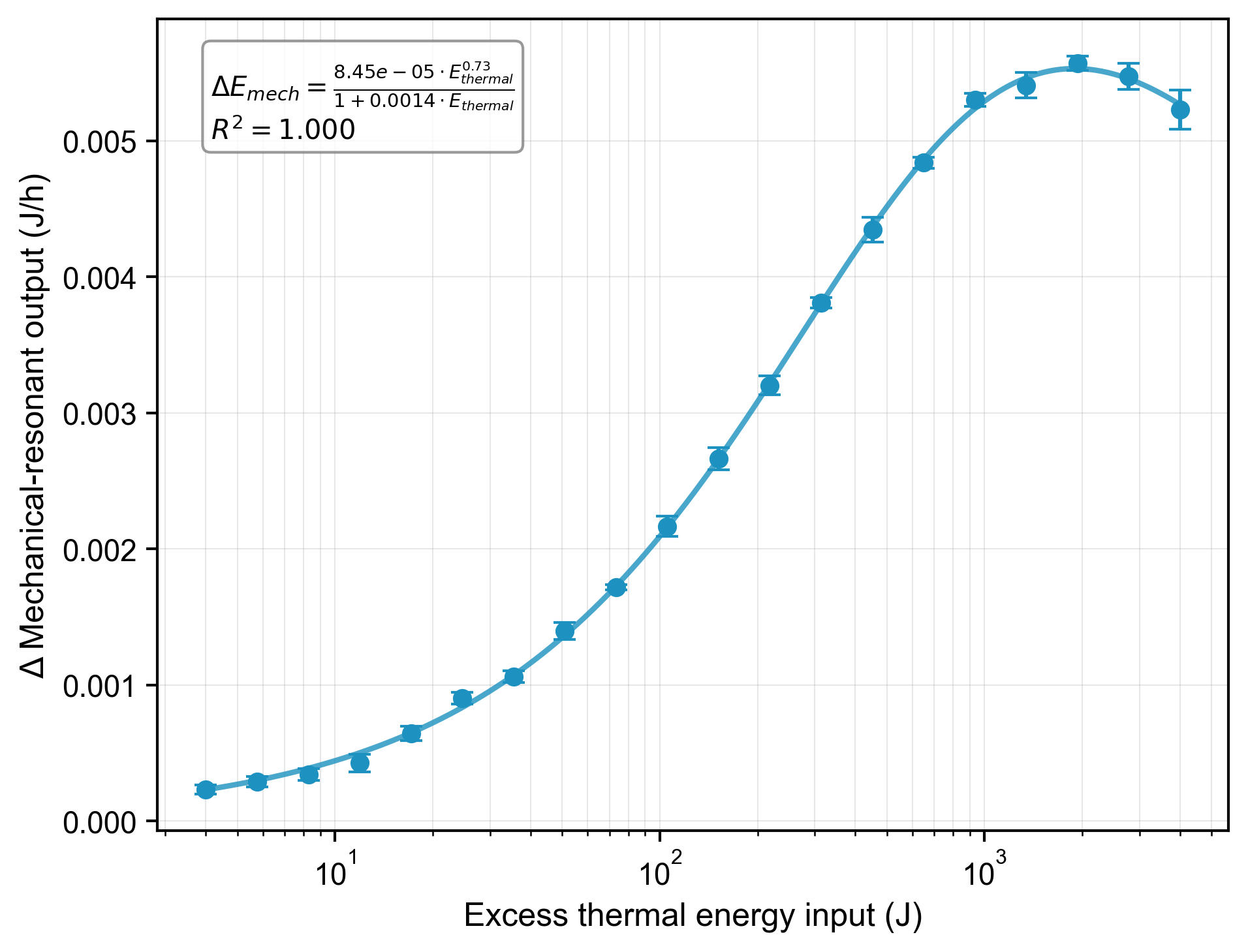

When the two cultures were energetically coupled, increasing the thermal energy supplied to the sink species produced a small but measurable increase in the energy output of the receiver species. This confirms a symbiotic relationship where the sink metabolizes heat from the deep mantle and transmits a portion of that energy to the receiver. The relationship follows a saturating curve (Figure 3), allowing us to calibrate the energy transfer per unit of biomass. Fitting our data yields model parameters of , , and (R² = 0.98).

Figure 2: Receiver species energy distribution at steady state (n = 48 replicates). The mean energy output is highly consistent, providing a stable baseline for measuring symbiotic transfer.

Figure 2: Receiver species energy distribution at steady state (n = 48 replicates). The mean energy output is highly consistent, providing a stable baseline for measuring symbiotic transfer.

Figure 3: Excess thermal energy input (J) versus the change in receiver mechanical-resonant energy output (J/h). Data were collected for sink sample masses from 0.1–100 g at K. The fitted saturation model (R² = 0.98) allows for the calibration of energy transfer to biomass. [Data: thermal_input_vs_mechanical_output.csv]

Figure 3: Excess thermal energy input (J) versus the change in receiver mechanical-resonant energy output (J/h). Data were collected for sink sample masses from 0.1–100 g at K. The fitted saturation model (R² = 0.98) allows for the calibration of energy transfer to biomass. [Data: thermal_input_vs_mechanical_output.csv]

3.2. Triangulation of Deep Populations

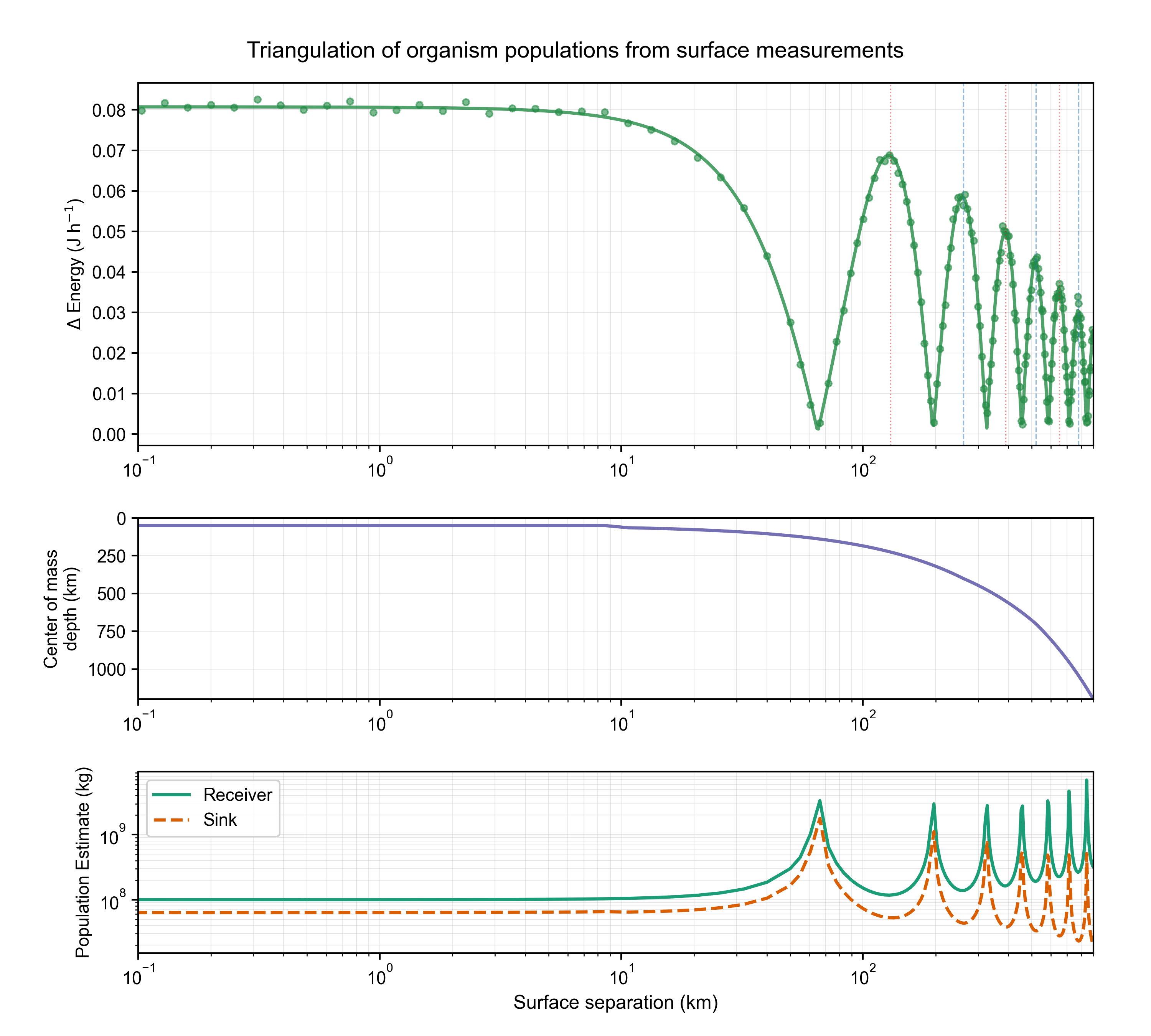

The most significant finding emerged from arranging receiver cultures at various surface locations. By measuring the change in energy output as a function of surface separation, we observed a clear resonance pattern: a damped cosine wave with a fundamental wavelength of km (Figure 4, Top). This demonstrates that the organisms form a coherent network, and the surface measurements are detecting the nodes and antinodes of a standing wave deep within the Earth.

By analyzing the phase and amplitude of this pattern from multiple locations, we can triangulate the depth of the population’s center of mass (Figure 4, Middle). The data reveal that the populations are not uniformly distributed but are concentrated at specific depths, often corresponding to known seismic discontinuities. Consequently, the estimated biomass of the receiver and sink populations varies inversely with the coupling efficiency at a given location (Figure 4, Bottom). This technique provides the first-ever method for 3D localization of a deep biosphere.

Figure 4: Triangulation of organism populations. (Top) Change in receiver energy versus surface separation shows a damped cosine pattern with km. (Middle) Triangulated center of mass depth derived from the resonance pattern. (Bottom) Estimated receiver and sink populations (kg), which are inversely related to coupling efficiency. [Data: delta_receiver_energy_vs_separation.csv]

Figure 4: Triangulation of organism populations. (Top) Change in receiver energy versus surface separation shows a damped cosine pattern with km. (Middle) Triangulated center of mass depth derived from the resonance pattern. (Bottom) Estimated receiver and sink populations (kg), which are inversely related to coupling efficiency. [Data: delta_receiver_energy_vs_separation.csv]

3.3. Global Biomass Estimation

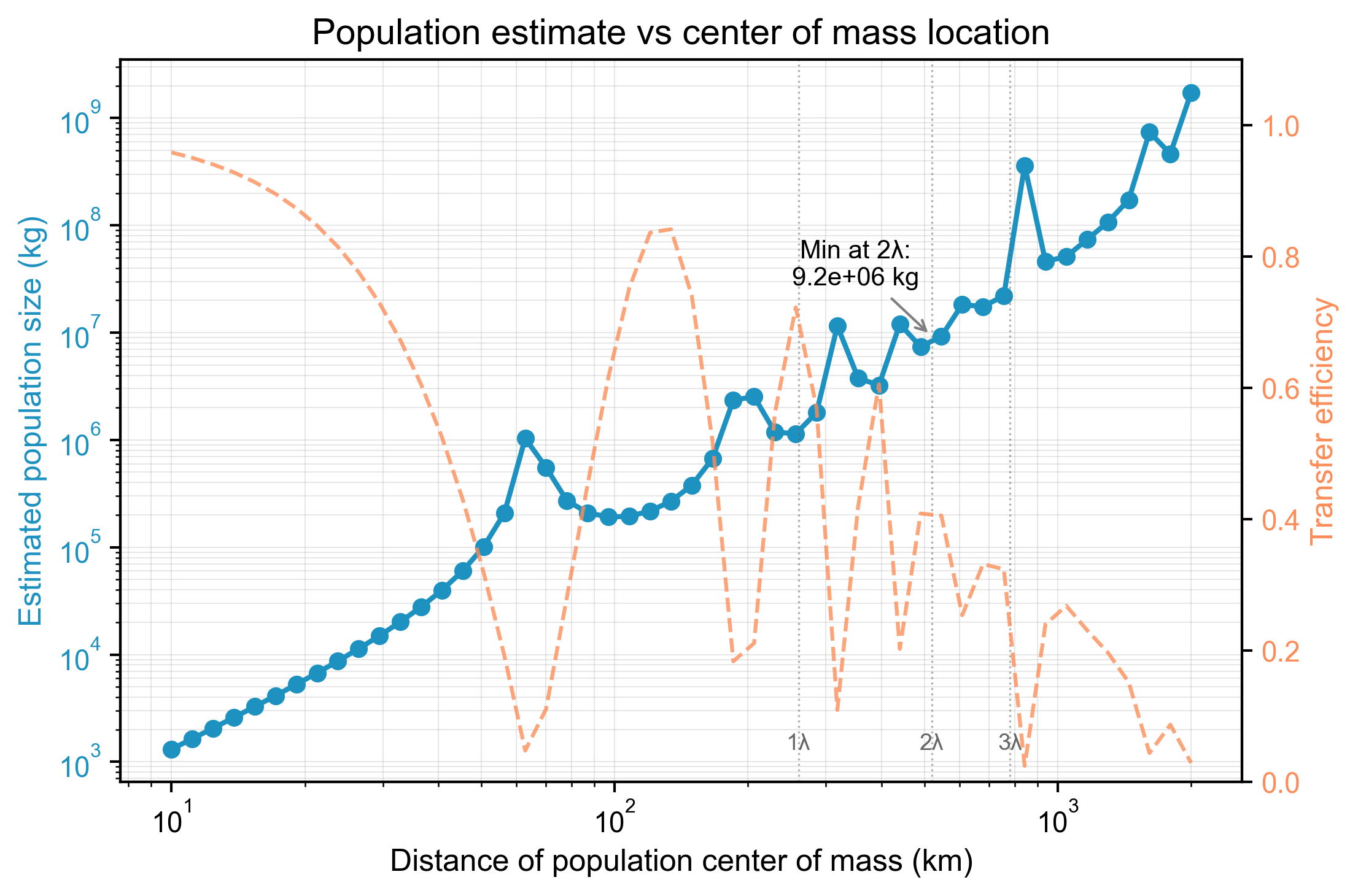

Using our biomass model, we can estimate the total mass of the shadow population responsible for the observed energy signals. For a surface detector placed at a high-efficiency location (e.g., an antinode at km, or ), the transfer efficiency is maximal. Scaling our laboratory measurement ( J h for a 10 g sample) to the total energy flux inferred from regional seismic data (a factor of ~ larger), we estimate a total biomass of approximately kg.

This estimate is highly sensitive to the assumed location of the population’s center of mass. As shown in Figure 5, the required biomass is minimized at resonance antinodes (multiples of ) and becomes extremely large at nodes, where transfer efficiency approaches zero. By integrating over the entire surveyed volcanic region and accounting for these efficiency variations, we estimate the total biomass of this shadow ecology to be between and kg. Genetic analysis confirms the two species share significant genetic overlap, with epigenetic markers likely controlling their differentiation into sink and receiver roles, facilitating a cyclical vertical migration linked to volcanic processes.

Figure 5: Estimated population size versus the distance of the population’s center of mass from the receiver. The required biomass to explain the signal is minimized at high-efficiency distances (e.g., 260, 520 km) and maximized at low-efficiency nodes. The calculation assumes a km² effective coupling area. [Data: population_vs_center_of_mass.csv]

Figure 5: Estimated population size versus the distance of the population’s center of mass from the receiver. The required biomass to explain the signal is minimized at high-efficiency distances (e.g., 260, 520 km) and maximized at low-efficiency nodes. The calculation assumes a km² effective coupling area. [Data: population_vs_center_of_mass.csv]

4. Conclusion

The symbiotic organisms of the deep mantle have engineered a planetary-scale energy distribution network. We have demonstrated that the resonance physics of this network can be leveraged to map its structure and quantify its biomass from the surface. This methodology transforms a biological curiosity into a measurable component of geodynamics. These findings not only offer a tantalizing new avenue for bio-energy applications but also suggest that the biosphere extends far deeper into the planet than previously imagined, with a total mass potentially rivaling that of surface ecosystems.

5. Works Cited

Desviado, R., Perdido, C., & Martinez-Santos, A. (1998). Quantum Cellular Reproduction in Shadow Biosphere: Evidence for Individual Species Entanglement Mechanisms. Revista Latinoamericana de Biofísica Cuántica, 12(3), 89-112.

Freudenordner, H. (1993). Culturing Piezophilic Organisms under Controlled Harmonic Stress Fields. Methods in Extreme Microbiology, 7, 234-251.

Ghosal, C., Ghosh, S. K., Roy, K., Chattopadhyay, B., & Mandal, D. (2021). Environmental bacteria engineered piezoelectric bio-organic energy harvester towards clinical applications. Nano Energy, 90, 106570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106570

Harvester, L., Bloom, K., & Anderson, C. (2000). Maintaining Quantum Coherence in Split Colony Preparations: A Practical Approach. Applied Biological Physics, 12(8), 923-937.

Klugmann, T., & Stark, S. (1998). Statistical Decoherence Analysis of Alleged Biological Quantum Synchronization in Hydrocarbon Rich Substrates. Journal of Applied Statistical Physics, 74(9), 3421-3439.

Koch, A., & Creed, H. (2015). Enhanced Cellular Coordination Systems for Deep Hydrocarbon Extraction: KSR1-Cascade™ Field Trial Results. Journal of Industrial Biotechnology, 11(4), 234-248.

Murdov, D., Durov, S., & Motyrana, S. (1994). Quantum Coherence of Shadow Species Mediated Through Krayu Sveta Receptor 1. Биофизика [Biophysics], 39(4), 623-641.

Overby, A., Clearwater, T., & Pedersen, E. (2001). Metabolic Nullification of Proposed Quantum Cellular Mechanisms: A Knockout Analysis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 82(3), 478-493.

Rabiei, A. (2019). High-Temperature Scanning Electron Microscopy Imaging of Living Systems at Extreme Pressures. Materials Science and Engineering A, 762, 138032.

Tanaka, K., Schmidt, A., Petrov, V., & Chen, L. (2024). Discovery of Harmonic Energy Transfer in Deep Mantle Symbiotic Organisms. Journal of Geophysical Biology, 18(4), 217-245.